In 1942, the literary critic and Princeton graduate, Edmund Wilson, then forty-seven, made friends with a scholar of Russian literature slightly younger than himself, Helen Muchnic. Born in Baku in 1902, Helen emigrated to the US as a child; after an intensely illustrious academic career, she was teaching at the elite Massachusetts women's college, Smith. Wilson did not usually like academics, but he took a shine to Muchnic. They started exchanging letters - about Gogol, Pushkin, Turgenev, everything and anything to do with Russian literature - as they would continue to do for the next thirty years, until Wilson's death in 1972 ('Do let us talk about Gogol when I see you. He is certainly a very strange man', Wilson wrote to Muchnic in 1943).

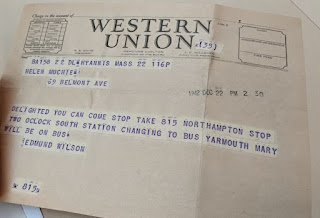

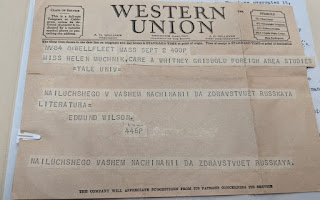

It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship that would outlast many books by each of them, many of Wilson's affairs and at least one of his marriages. They soon progressed from Dear Miss Muchnic to Dear Helen, a level of familiarity that would endure (Wilson never signed off with his nickname 'Bunny', dropping his surname only in the final decade of their correspondence). At the time they met, Wilson was still married to his third wife, the novelist and critic Mary McCarthy. By December 1942, Muchnic was a welcome guest at the Wilson-McCarthy household: on December 22 that year,Wilson sent her a telegram with instructions for reaching their home at Wellfleet, near the tip of Cape Cod, where he famously hid out from the hothouse of New York society. After catching various trains, Helen was to change onto a bus in Yarmouth: 'Mary will be on bus'. The mere idea of hailing a bus on which Mary McCarthy is already seated, to progress to an intimate dinner with the cream of East Coast intelligentsia, baffles my saurian brain. Yet, clearly, Helen Muchnic held her own, and brought vegetables, too. In summer 1943, Wilson followed up another dinner with this note:

'I have delayed answering your letter and thanking you for the radishes because I had to go away for a week and got no chance to write any letters. First of all, we were delighted with the radishes. I am especially fond of radishes, and these are the best I have had for years. When I was a child, I used to cut them in little slices and eat them on bread and butter, and I ate a great many of these that way (made the better part of a lunch and a supper on them). Many of the radishes you buy or get in restaurants have been allowed to get too big and coarse, and the taste is too sharp. You seem to have pulled these at just the right time'.

The rest of the letter is about Thomas Hardy, Allen Tate, and Antigone. Later that same year Wilson added: 'We have been having a wonderful time with your vegetables. We have had some wonderful novelties such as Vichysoisse soup made out of sorrel or squash, and slices of squash fried or something in a way that is delicious. They really have been a great treat'. This letter has two added scribbles: a ragged one from Wilson about Dostoevsky's sense of humour, and a neat cursive addendum by Mary McCarthy: 'Edmund has already mentioned the vegetables to you - the lettuce was heavenly and this time came through well, Is the small spear-like one romaine or a new variety of lettuce?' While there have been various accounts of the Wilson-McCarthy marriage and its discontents (including two by their son Reuel), their relationship has surely never been viewed before from the perspective of mutual salad appreciation.

Several months after the radish and romaine revel, on October 23rd, Wilson invited Muchnic to see a version of Gogol's The Fair at Sorochinsk 'at the Russian ballet'; he asked her to queue for the tickets, but enclosed a cheque to cover the costs. As an apparent afterthought, he scrawled under his signature: 'They have offered me Clifton Fadiman's job reviewing books on the New Yorker, & I've decided to take it for a year, though I doubt whether anything good but money will come of it'. On August 7th, 1944, Wilson wrote to Helen: 'The Nabokovs are here in Wellfleet [...]. Vladimir & I have been giving each other quizzes on our respective languages. Here is one of his more interesting questions. How would you answer it? Put into Russian the following sentence: At the harbor I saw many masts and had many day-dreams (using мечта for day-dream)'. Thus, with a scribble and a pun or two, historic literary relationships were forged.

By February 1945, when Wilson was finishing a book (presumably Europe Without Baedeker) while managing New Yorker reviews, his tone regarding Mary had changed: '[...] don't take too seriously anything Mary may have said, when you saw her. Her way of seeing herself in a drama doesn't always make connections with reality. Lately she has been acting out a novel when she ought to be writing one'. By October that year, he confided that his teenage daughter 'Rosalind has just moved in with me and we have been having quite a good time together fixing the place up'; Muchnic was already settled in a senior position at Smith, where she had started as an instructor in Russian in 1930, aged 28. The following year, 1946, Wilson was trying to get a divorce so as to marry yet again, to Elena Mumm Thornton, of the Mumm champagne dynasty. Elena was a member of the Struve family and a native Russian speaker; her grandfather had been the Russian ambassador to Japan. In his letters to Muchnic, Wilson fretted that Mary might 'obstruct it' (the wedding) with more fuss 'in court over nothing'. Clearly, Mary was no longer on the bus. In May 1948 Wilson shared the news of his and Elena's new baby, and asked if Muchnic had heard that Vladimir Nabokov would soon start teaching Russian at Cornell ('They are immensely pleased about it , as it means a good salary, & it happens to be one of the only colleges where serious work with butterflies is done'). But by 1955, the friendship with Nabokov was challenged by Wilson's adverse reaction to Lolita: ‘I was disappointed in Volodya Nabokov’s new novel and for that reason I don’t think I’ll review it [in the New Yorker]’. It seems a shame that he couldn't have managed a concise review like that offered by Mr Brundish in Penelope Fitzgerald's tragic novella The Bookshop (1978): 'I have read Lolita, as you requested. It is a good book, and therefore you should try to sell it'. And of course, by 1963, Wilson and Nabokov were official literary enemies.

Muchnic and Wilson, by contrast, were still good chums; if anything, their friendship grew warmer, with Wilson signing off 'love, Edmund' (love was often sent to Muchnic's partner Dorothy as well); mansplaining to her how to write in the 'terse' style he preferred; and asking her views on exactly what Vronsky was thinking, among other burning Russian literary questions, to the very end. He even awarded her an unofficial prize for best Christmas card in 1956 (perhaps it featured seasonal radishes). Muchnic continued dedicating her books to him, to Wilson's mild disapproval (it meant he couldn't review them personally). In a somewhat enigmatic interlude, the manager of Fort Schuyler - a private gentleman's club in Utica, New York - wrote to Edmund Wilson in 1970 to follow up what he called a '"fender-bending" incident' in October 1969, 'involving your secretary's car and a parked car, [which] has not been resolved. [...] Apparently, through some oversight, Miss Helen Muchnic failed to turn in an accident report to her insurance company [...]. Anything you could do to speed this process up would be greatly appreciated'. Was Muchnic meeting Wilson at his club, and did she prang her car before or after lunch? Why was she described as Wilson's 'secretary', and why were her academic titles neatly elided? Possibly she was driving Wilson, who must have been frail and who would soon afterwards suffer a stroke, to his club. Wilson sent this note from the club manager to Muchnic, but although he scribbled on it, he confined his commentary to thoughts on 'the exiled Sinyavsky', so we remain no wiser about the fender-bender.

Wilson did his best to mentor Muchnic's career, suggesting to Yale that they should hire her (and Nabokov) as lecturers 'on special subjects', writing her a reference for Bennington College in Vermont in 1944 when she was evidently contemplating a sideways move (his daughter had studied there). In 1947, he congratulated Muchnic on the appearance of her book: 'Reading you has had the effect of making me want to go back to Russian literature'. This would have been her Introduction to Russian Literature, published by Doubleday in 1947. Later, he would call her 1961 book From Gorky to Pasternak: Six Writers in Soviet Russia 'the best book on the subject in any language'. However, Muchnic pursued a robust career at Smith - with cameos at other institutions, including Vassar, her undergraduate college, UCL SSEES in London, Bryn Mawr, where she took her PhD, and Yale (where she briefly taught) - without Wilson's patronage, rising by 1947 to full professor at Smith and becoming chair of Russian there in 1963, a position she held until her retirement in 1969. In fact, the patronage may have worked better the other way round; letters from 1966 seem to indicate that Muchnic may have recommended Wilson and McCarthy's son Reuel for teaching posts at Toronto and elsewhere (he eventually became a professor of Slavic literature at the University of Western Ontario).

Muchnic must have encountered Sylvia Plath, since the latter studied at Smith between 1950 and 1955 and wrote her thesis on Dostoevsky. Muchnic was certainly friendly, over many years, with Vassar buddy Elizabeth Bishop, as correspondence in their respective archives (held at Smith and Vassar respectively) attests. Muchnic published three more books in the course of her long career (including Dostoevsky's English Reputation, which I have cited in my own work); besides her Wilson-invited reviews in the New Yorker, she also published extensively between 1968 and 1980 on Russian fiction in the iconic New York Review of Books (one 1977 headline reads, 'Was Gogol Gay?'). Muchnic spent most of her life in a relationship with a woman, her Smith colleague Dorothy Walsh; an orientation which very likely protected and prolonged her friendship with the notoriously philandering Wilson. She died in 2000. Predictably, most professional interest in Wilson's correspondence has focused on exchanges with fellow literary lions, like Nabokov (see Simon Karlinsky's Dear Bunny, Dear Volodya: The Nabokov-Wilson Letters, 1940-1971) or McCarthy. His long and low-profile friendship with Muchnic, however, offers insights into his lifelong enthusiasm for Russian language and literature, as well as unexpected angles on his career, his literary attachments, his family, and, of course, the radishes.

Acknowledgements: I thank Princeton University's Firestone Library for access to their archive of Wilson-Muchnic letters (1941-72, Boxes 1-2). This account may appear one-sided because the Firestone holds only Wilson's side of the correspondence; I am unclear whether Muchnic's letters to him have been preserved.